Platforms: Linux, Windows, macOS (Terminal/CLI)

License: Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Languages: C, Python, Rust, BASIC (QB64, FreeBASIC)

Author: George McGinn

GitHub: https://github.com/GeorgeMcGinn/MoonLander (Source Code & Binaries)

On July 20, 1969, Neil Armstrong’s heartbeat doubled as he manually guided Apollo 11’s Lunar Module to a safe landing with just 30 seconds of fuel left. Now, developers can relive that tension in an open-source terminal game written in C, Python, QB64, and FreeBASIC. This multi-language project fuses 1960s aerospace engineering with modern physics simulation, offering a unique blend of history, science, and interactive gameplay.

About the Game: A Cross-Platform Time Machine

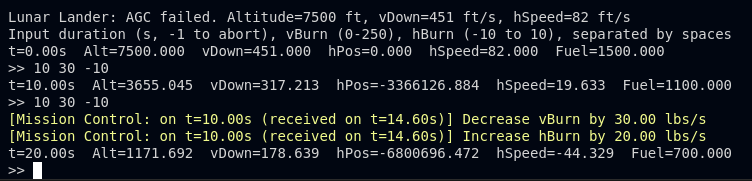

In this simulator, the Apollo Guidance Computer (AGC) fails at 7,500 feet, forcing you to manually land the Lunar Module with randomized velocities. Beneath its simple terminal interface lies a physics engine that echoes the Apollo era, complete with historically accurate constants like lunar gravity (5.33136483 ft/s²) and exhaust velocity (10,000 ft/s). The game’s realism is further enhanced by a 4.6-second communication delay, simulating the challenges Apollo astronauts faced.

Key Realistic Elements

- Lunar gravity: 5.33136483 ft/s²

- Exhaust velocity: 10,000 ft/s

- 4.6-second Mission Control delay

Real-World Physics

- Tsiolkovsky equation for fuel consumption

- Runge-Kutta 4 (RK4) integration for precision

- Newton’s second law using mass in slugs

Gameplay Mechanics: Become the AGC

Players enter commands like: [Duration] [vBurn] [hBurn]

Lunar Lander: AGC failed. Altitude=7500 ft, vDown=451 ft/s, hSpeed=82 ft/s

>> 3.5 180 -4 (3.5s burn, 180 lb/s vertical, -4 lb/s horizontal)

Note: BASIC versions use commas instead of spaces.

No Two Games The Same

At the start of each game, the initial vertical speed (vDown, 200-700 ft/s) and horizontal speed (horizSpeed, 50-200 ft/s) are randomized using a random number generator. This variability mirrors the unpredictability of real lunar landings, where factors like thruster misalignment or gravitational anomalies could influence descent, ensuring a unique challenge every time.

Why Add Randomness?

This randomization captures the uncertainty of actual lunar missions, where variables like fuel consumption or terrain could shift unpredictably. By varying vDown and horizSpeed within these ranges—chosen to balance difficulty and achievability—the game avoids predictable patterns. Players must adapt to fresh conditions each time, boosting playability and making every landing feel like a new mission.

How It Keeps the Game Challenging

The randomized speeds create dynamic difficulty. A high vDown might demand aggressive thruster burns to slow descent, risking fuel depletion, while a high horizSpeed requires precise lateral adjustments to avoid overshooting the landing zone. For example, a high vDown with low horizSpeed might call for early vertical corrections, whereas low vDown with high horizSpeed shifts focus to countering drift. This variability keeps players on their toes, rewarding quick thinking and adaptability over rote memorization.

The physics engine calculates vertical and horizontal dynamics using real-time equations, such as net acceleration and velocity changes based on burn rates.

The 4.6-Second Lag: A Nod to History

The game enforces a 4.6-second delay (2.6s for Earth-Moon signal travel + 2s processing), mimicking Apollo’s communication limits and forcing players to rely on predictive thinking. Here’s how it compares to the real Apollo missions:

| Component | Real Apollo | Game Simulation |

|---|---|---|

| Signal travel time (Earth-Moon) | 2.6 seconds | 2.6 seconds |

| Mission Control processing | 4-6 seconds | 2 seconds |

| Total feedback delay | 6.6-8.6 seconds | 4.6 seconds |

This delay was a balancing act during development—long enough to feel authentic, but short enough to keep the game engaging. Testing it myself, I found the lag forced me to think ahead, adding tension that mirrored the Apollo missions.

The Physics Engine: RK4 vs. Heun’s Method

While the AGC used Heun’s method due to hardware constraints, this game employs RK4 for superior accuracy (0.01% error vs. 1.6%). Using RK4 simulates what NASA ran on the IBM 360 Mainframes. Detailed steps are available in our technical docs.

Fuel Management: Two-Stage Design

Descent Stage

- Fuel: 1,500 lbs

- Burn: 0-250 lb/s

- Dry mass: 4,700 lbs

Ascent Stage

- Fuel: 5,187 lbs (abort only)

- Dry mass: 4,850 lbs

Aborting uses Tsiolkovsky’s equation to calculate escape velocity, ensuring realism in emergency scenarios.

Historical Accuracy vs. Gameplay

Authentic

- ✅ Two-stage fuel system

- ✅ Exhaust velocity

- ✅ Communication delay

Simplified

- ❌ Flat terrain

- ❌ Basic thrust mechanics

- ❌ No mascons

Comparing moonLander to Classic BASIC Games

In the 1970s and 1980s, Creative Computing magazine introduced players to the thrill of space exploration with two iconic BASIC games: LUNAR and LEM. These early simulations captured the imagination of players by letting them pilot a lunar module to the Moon’s surface. moonLander builds on this legacy with advanced features and a focus on realism. The table below compares moonLander with LUNAR and LEM, exploring their gameplay, scientific accuracy, and the unique elements that make moonLander a standout evolution of the genre.

| Category | moonLander (C, Python & BASIC) | LUNAR.BAS | LEM.BAS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gameplay Mechanics |

|

|

|

| Physics Simulation |

|

|

|

| Realism and Features |

|

|

|

| Educational Value |

|

|

|

| Engagement |

|

|

|

Developer’s Notes: Slugs, Delays, and Design Choices

Mass Slugs in the Physics Engine

The game uses slugs for mass, a unit tied to the Apollo program’s engineering roots. Slugs—where 1 slug accelerates at 1 ft/s² under 1 lbf—match the US customary units of the 1960s, like pounds-force for thrust and feet for distance. NASA engineers relied on slugs to simplify calculations, such as thrust acceleration (\( a = \frac{F}{m} \)), avoiding the unit conversions SI would require. This choice keeps the physics engine consistent and historically authentic.

The Time Delay Challenge

The 4.6-second delay (2.6s signal travel + 2s processing) mirrors Apollo’s communication lag. In real missions, delays could hit 6-8 seconds, but I chose 4.6 seconds to balance realism and playability. During testing, I often found myself second-guessing my inputs, knowing the feedback would arrive too late to react in the moment—a challenge that made every successful landing feel earned.

Why Randomize Speed Variables

One of the main drawbacks of other lunar lander games, from those played in the 1970’s and programs printed by Creative Computing magazine, once you figure out how to play, and what values work, that’s it for the game. Back in 1973 I made similar modifications to the BASIC game LEM that was on the DEC PDP/8E at my high school. Also these games really don’t conform to phsyics. In writing this game, I wanted it to be both challenging and true to science. I picked the starting altitude at 7,500 feet with a different vDown and horizSpeed, but keep the same amount of fuel. It is at 7,500 feet that the LEM started it’s landing burns, and it had about 1,200 to 1,500 lbs of fuel left. No two games will be the same. You can make the game even more challenging by randomizing both the starting altitude and fuel. I may make those changes in a future release.

Balancing Gameplay and Realism

Accuracy matters, but gameplay trumps all. Slugs and delays are nod to history, yet I skipped complex features like mascons to keep controls intuitive. One of my own crash landings—misjudging a burn by just a second—taught me the value of precision, and I knew players would feel the same thrill (and occasional frustration) when they play. I can say that even though I coded this game and spend weeks testing it, I’ve only successfully landed once!

More Than a Game—A Living History

This isn’t just a simulator; it’s a time capsule. Each command connects players to Apollo’s legacy, blending code with history. For me, it’s personal: watching Armstrong’s steps as an 11-year-old and playing and modifying a LEM program in 9th grade inspired this project. It’s my way of sharing that wonder.

Technical Challenges: Coding the Physics Engine

Coding RK4 integration was tricky but rewarding. I tuned time steps to 0.1 seconds for accuracy without slowing older systems. The engine now runs smoothly, keeping the game accessible across platforms. And it closely simulates what the IGM Mainframe at NASA would use to calculate a predicted landing on the Moon.

Conclusion: A Tribute to Apollo

This simulator honors Apollo’s physics and spirit. The C version works on Raspberry Pis and old PCs, while Python and BASIC invite tinkering. Check the code on my GitHub and explore the science in our technical docs.

Copyright ©2025 by George McGinn. All rights reserved.