Platforms: Commodore 64, C64 & 128 (in C64 mode)

License: Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Languages: Commodore BASIC v2.0

Author: George McGinn

GitHub: https://github.com/GeorgeMcGinn/MoonLander/tree/main/commodore64

Introduction

The Apollo Moon Lander simulator represents a fascinating journey through computing history, evolving from a modern C implementation to two distinct Commodore 64/128 BASIC programs: a text-based input version and a real-time joystick control version. This project demonstrates not only the timeless appeal of space simulation but also the challenges and rewards of adapting sophisticated numerical simulations to the constraints of 1980s home computing hardware.

Historical Context and Evolution

The Original Vision

The Apollo Lunar Lander simulator began as a C program designed to recreate the critical moments of Apollo lunar landings. The original concept was inspired by the real challenges faced by Apollo astronauts if the Apollo Guidance Computer (AGC) would fail or require manual override during the final descent phase.

The simulation places the player in the role of an Apollo astronaut whose AGC has failed at 7,500 feet above the lunar surface. With the spacecraft carrying random initial velocities (200-700 ft/s downward, 50-200 ft/s horizontal) from emergency burn errors, the player must manually control the Lunar Module’s descent engines to achieve a safe landing.

Multi-Platform Evolution

The project’s evolution across multiple platforms tells a story of both technological advancement and the enduring appeal of retro computing:

- C Implementation: The original version leveraged modern computing power to implement sophisticated numerical methods, including 4th-order Runge-Kutta (RK4) integration for highly accurate physics simulation.

- QB64 Port: The program was subsequently ported to QB64, maintaining the advanced numerical methods while providing a more accessible development environment and modern compatibility.

- Python Version: A Python implementation was also developed, taking advantage of that language’s mathematical libraries and ease of development.

- Commodore 64/128 Text-Based Version: The first C64 adaptation maintained the turn-based input system from the original C program.

- Commodore 64/128 Real-Time Joystick Version: An implementation featuring true real-time control with joystick input, representing a complete reimagining of the user interface for authentic 1980s gaming experience.

Commodore 64 Implementations

Version 1: Text-Based Input System

The initial C64 adaptation closely followed the original C program’s turn-based gameplay, where players input burn duration and thrust values via keyboard. This version served as the foundation for understanding the computational constraints and optimization techniques required for the platform.

Version 2: Real-Time Joystick Control System

The real-time version represents a complete paradigm shift, transforming the simulation from a turn-based strategy game into an action-oriented real-time piloting experience.

Real-Time Features

Continuous Control System:

- 10 frames per second update rate (0.1-second intervals)

- Real-time joystick input via Commodore 64 Control Port 2

- Immediate thrust response with variable acceleration rates

- Live Mission Control guidance during flight

Emergency Response System:

- High-Speed Emergency Mode: When vertical speed ≥400 ft/s, vertical thrust increases at 10 lbs/s per 0.1-second frame instead of 1 lb/s

- High-Thrust Reduction Mode: When vertical thrust >30 lbs/s, thrust decreases at 5 lbs/s per frame instead of 1 lb/s for rapid power reduction

- Emergency Mission Control: Additional guidance messages every 1 second during dangerous descent speeds

Physics-Accurate Mission Control:

- Signal Delay: 1.3 seconds (speed of light Earth-Moon)

- Processing Time: 4.0 seconds (Ground Control analysis)

- Return Signal: 1.3 seconds (speed of light Moon-Earth)

- Total Delay: 6.6 seconds from telemetry capture to message display

Advanced Trajectory Analysis:

- Independent vertical and horizontal correction calculations

- Support for vburn-only, hburn-only, or combined corrections

- “Nominal” confirmation when trajectory is acceptable

- Continuous monitoring with smart message queuing

The Commodore 64 Challenge

Hardware Constraints

The Commodore 64, while revolutionary for its time, presented significant computational limitations for a physics simulation:

- CPU: 1 MHz MOS 6510 processor

- RAM: 64KB total system memory

- Floating Point: Software-based arithmetic through BASIC interpreter

- Performance: Dramatically slower than modern systems

- Input: 2-button joystick with 4-direction control

These constraints necessitated fundamental changes to the simulation approach while maintaining scientific accuracy and engaging gameplay.

Algorithmic Adaptations

From RK4 to Euler Integration

The most significant technical adaptation was the replacement of 4th-order Runge-Kutta integration with simplified Euler integration:

Original RK4 Method:

k1 = f(t, y) k2 = f(t + h/2, y + h*k1/2) k3 = f(t + h/2, y + h*k2/2) k4 = f(t + h, y + h*k3) y_new = y + h*(k1 + 2*k2 + 2*k3 + k4)/6

C64 Euler Method:

y_new = y + h*f(t, y)

This change reduced computational complexity from 4 function evaluations per time step to 1, achieving approximately 4× speed improvement while maintaining sufficient accuracy for gameplay.

Real-Time Display Optimization

The real-time version implements sophisticated display management:

Cursor Positioning System:

poke 211,18:poke 214,5:sys 58640:print " "; poke 211,18:poke 214,5:sys 58640:print int(ct*10)/10

Performance Considerations:

- Values cleared with spaces before updating to prevent visual artifacts

- SYS 58640 calls for precise cursor positioning

- Selective updates only for changed values

Mission Control Message Queuing

Both versions implements a sophisticated message queue system:

- Maximum 10 pending messages

- Automatic message removal after display

- Support for overlapping guidance periods

- Independent correction calculations for vertical and horizontal axes

Scientific Foundations

Lunar Physics

The simulation implements accurate lunar environment physics:

- Lunar Gravity: 5.33 ft/s² (compared to Earth’s 32.174 ft/s²)

- Vacuum Environment: No atmospheric drag or weather effects

- Mass-Variable Dynamics: Spacecraft mass changes as fuel is consumed

Spacecraft Dynamics

The simulation models the complete Apollo Lunar Module system:

Descent Stage:

- Dry Mass: 4,700 lbs

- Fuel Capacity: 1,500 lbs

- Engine: Variable thrust 0-250 lbs/s vertical, ±10 lbs/s horizontal

Ascent Stage (for abort scenarios):

- Dry Mass: 4,850 lbs

- Fuel Capacity: 5,187 lbs

- Abort Capability: Can reach lunar orbit (5,512 ft/s)

Rocket Equation Implementation

The simulation correctly implements Tsiolkovsky’s rocket equation for abort scenarios:

Δv = Ve * ln(m_initial / m_final)

Where:

- Ve = Exhaust velocity (10,000 ft/s)

- m_initial = Total mass before burn

- m_final = Dry mass after fuel depletion

Mission Control Simulation

Communication Delay

One of the simulation’s most authentic features is the implementation of realistic communication delays:

- Signal Delay: 1.3 seconds (Earth-Moon signal travel time at speed of light)

- Processing Delay: 4.0 seconds (Ground Control analysis time)

- Return Signal: 1.3 seconds (Moon-Earth signal travel time)

- Total Delay: 6.6 seconds

This delay system queues Mission Control corrections and displays them at historically accurate intervals, forcing players to make decisions with delayed information—exactly as real Apollo astronauts experienced.

Advanced Guidance Algorithm

Mission Control feedback in the real-time version uses sophisticated trajectory analysis:

- Independent Axis Analysis: Vertical and horizontal corrections calculated separately

- Proportional Feedback: Correction magnitude proportional to velocity error

- Smart Messaging: Only sends corrections when needed, “nominal” when trajectory acceptable

- Emergency Protocols: More frequent guidance during dangerous descent phases

Real-Time Version Technical Implementation

Hardware Requirements

Minimum Configuration:

- Commodore 64 or Commodore 128 (in C64 mode)

- Digital joystick in Control Port 2

- Standard TV or monitor

Control System

Joystick Controls:

- UP: Decrease vertical thrust (1 lb/s normal, 5 lb/s when thrust >30 lbs/s)

- DOWN: Increase vertical thrust (1 lb/s normal, 10 lb/s when speed ≥400 ft/s)

- LEFT: Thrust left (decrease horizontal velocity)

- RIGHT: Thrust right (increase horizontal velocity)

- FIRE BUTTON: Abort to orbit (hold for 0.3 seconds to prevent accidental activation)

Emergency Response Rates:

- High-Speed Mode (≥400 ft/s): Vertical thrust increases 10× faster

- High-Thrust Mode (>30 lbs/s): Thrust reduction 5× faster

- Normal Mode: 1 lb/s per 0.1-second frame

Display System

Real-Time Dashboard:

Update Frequency:

- Flight Data: Every 0.1 seconds (10 FPS)

- Mission Control: Checked every frame, displayed when ready

- Trajectory Analysis: Every 2 seconds (normal), every 1 second (emergency)

Performance Optimization

Real-world testing on authentic Commodore 64 hardware revealed optimizations:

- Button Debouncing: 3-frame requirement (0.3 seconds) for abort button

- Display Efficiency: Selective cursor positioning and value clearing

- Memory Management: Fixed arrays and compact variable names

- Computational Limits: Maximum 20 simulation steps per game loop iteration

Mission Control Protocol

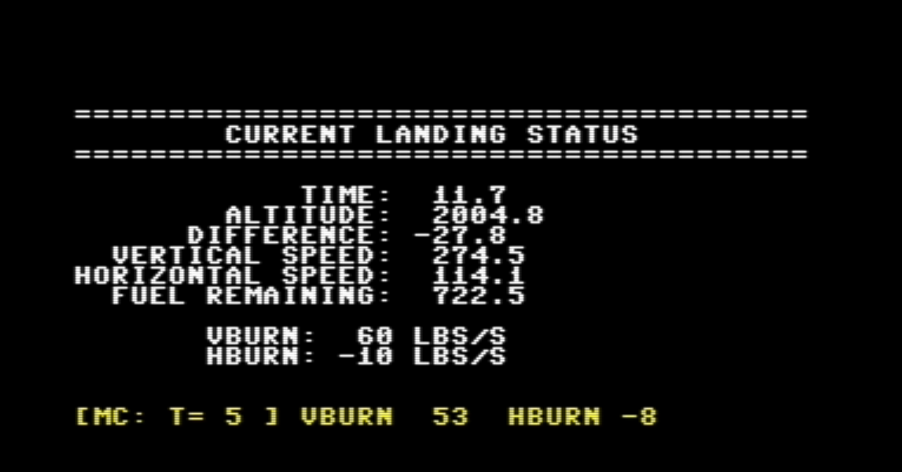

Message Format:

[MC: T= 5 ] VBURN 53 HBURN -8

Message Types:

- Correction Messages: Specific thrust adjustments needed

- Nominal Confirmation: “nominal” when trajectory is acceptable

- Emergency Guidance: More frequent messages during dangerous phases

Timing Protocol:

- Analysis triggered every 2 seconds (normal) or 1 second (emergency)

- 6.6-second delay from analysis to message display

- Messages displayed immediately when ready (no additional queuing delay)

How to Play

Game Setup

- Hardware Connection: Connect joystick to Control Port 2

- Program Loading: Load and run the BASIC program

- Initial Conditions: Note starting altitude (7,500 ft), vertical speed (200-700 ft/s), and horizontal speed (50-200 ft/s)

Gameplay Objectives

Primary Goal: Land safely with both vertical and horizontal speeds ≤5 ft/s

Landing Classifications:

- Perfect Landing: Vertical ≤5 ft/s, Horizontal ≤5 ft/s

- Good Landing: Vertical ≤15 ft/s, Horizontal ≤15 ft/s

- Crash Landing: Excessive impact speed

Strategy Guide

Phase 1 – Initial Assessment (0-10 seconds):

- Observe initial velocities displayed at startup

- Begin gentle thrust adjustments to test responsiveness

- Wait for first Mission Control guidance at ~8.6 seconds

Phase 2 – Emergency Response (High Speed Phases):

- If vertical speed ≥400 ft/s, utilize 10× thrust increase rate

- Build vertical thrust quickly to counteract dangerous descent

- Monitor Mission Control for emergency guidance (every 1 second)

Phase 3 – Trajectory Correction (Mid-Flight):

- Follow Mission Control guidance for vburn and hburn adjustments

- Remember 6.6-second delay between your actions and their assessment

- Make gradual adjustments rather than rapid changes

Phase 4 – Final Approach (Low Altitude):

- Target vertical speed ~10-15 ft/s for final descent

- Minimize horizontal speed to near zero

- Use high-thrust reduction mode (5× faster) when vburn >30 lbs/s

Phase 5 – Touchdown (Final 100 ft):

- Fine-tune both vertical and horizontal velocities

- Aim for ≤5 ft/s in both axes for perfect landing

- Maintain slight downward thrust until surface contact

Advanced Techniques

Fuel Management:

- Monitor fuel remaining continuously

- Plan abort scenarios before fuel depletion

- Remember: ascent fuel only available for abort, not landing

Mission Control Integration:

- Use delayed guidance to plan future corrections

- Don’t overcorrect – small adjustments are more effective

- Learn to anticipate needed corrections based on current trajectory

Emergency Procedures:

- Abort Protocol: Hold fire button for 0.3 seconds

- Minimum Abort Altitude: 100 ft (below this, abort will fail)

- Abort Success: Requires sufficient Δv to reach 5,512 ft/s orbital velocity

Common Challenges

Emulator vs. Hardware:

- Joystick response may vary between VICE emulator and real C64

- Button debouncing compensates for emulator timing issues

- Real hardware typically provides more responsive control

Timing Strategy:

- Account for 6.6-second Mission Control delay in planning

- Start major corrections early in descent

- Fine adjustments become more critical at lower altitudes

Physics Intuition:

- Lunar gravity is much weaker than Earth gravity

- Small thrust changes have significant cumulative effects

- Horizontal motion requires active correction (no atmospheric drag)

Legacy and Modern Relevance

Retro Computing Renaissance

The real-time C64 implementation arrives during a renaissance in retro computing, where enthusiasts seek authentic experiences on original hardware. This project demonstrates that complex simulations can be meaningfully adapted to vintage systems without sacrificing educational or entertainment value, while adding genuine real-time control that wasn’t possible in the original Apollo era.

Historical Accuracy

By implementing real-time joystick control with authentic communication delays, the project creates an experience closer to what Apollo astronauts actually faced than the original turn-based versions. The combination of immediate physical control with delayed guidance information authentically recreates the isolation and pressure of lunar landing.

Modern Applications

The optimization techniques and real-time control systems developed for the C64 version have relevance in modern embedded systems, IoT devices, and educational environments where computational resources remain constrained. The emergency response algorithms demonstrate adaptive user interface design principles applicable to modern safety-critical systems.

Conclusion

The Apollo Lunar Lander Simulator for Commodore 64 represents more than a simple game port—it’s a bridge between computing eras that demonstrates the timeless nature of good programming and simulation design. The evolution from text-based input to real-time joystick control shows how technological constraints can drive innovation, ultimately creating more engaging and authentic user experiences.

The real-time version achieves something the original Apollo program could not: it gives players immediate physical control over the spacecraft while maintaining the authentic communication delays and decision-making pressures faced by real astronauts. This combination creates a unique historical simulation that is both technically accurate and viscerally engaging.

By successfully adapting sophisticated numerical methods to 1980s hardware constraints while adding genuine real-time control, the project shows that the fundamental challenges of physics simulation and human-machine interaction transcend technological generations. The result is a program that honors both the computational elegance of the Apollo program and the creative potential of 1980s home computing.

For modern programmers, the project serves as a masterclass in optimization and real-time system design, demonstrating that creative solutions emerge from tight constraints. For space enthusiasts, it provides an authentic taste of the split-second decision-making that defined humanity’s greatest adventure. For retro computing enthusiasts, it represents the pinnacle of what’s possible when combining period-appropriate hardware with modern software engineering insights.

The Apollo Lunar Lander Simulator stands as proof that great ideas—whether they involve landing on the Moon or simulating the experience on a home computer—can transcend the limitations of their time and continue to inspire new generations of explorers, programmers, and dreamers.

Technical Specifications

System Requirements

- Hardware: Commodore 64 or 128 (C64 mode), digital joystick (Control Port 2)

- Memory: Standard 64KB configuration

- Display: 40×25 character display, color or monochrome

- Storage: Floppy disk, tape, or modern storage solutions (SD2IEC, etc.)

Performance Characteristics

- Update Rate: 10 frames per second (0.1-second intervals)

- Input Latency: Single-frame response (0.1 seconds maximum)

- Mission Control Frequency: Every 2 seconds (normal), every 1 second (emergency)

- Display Refresh: Real-time updates with optimized cursor positioning

Program Statistics

- Lines of Code: ~260 lines of BASIC

- Memory Usage: <8KB including variables and arrays

- Execution Speed: Optimized for 1 MHz 6510 processor

- File Size: ~6KB saved program

The Apollo Lunar Lander Simulator for Commodore 64 v1.0.0 is available as open source software, continuing the tradition of sharing knowledge that made the original Apollo program possible. Check the code on my Commodore 64 Lunar Lander GitHub.

Copyright ©2025 by George McGinn. All rights reserved.

Keywords: moon lander, Apollo physics, RK4, rocket equation, open-source